Successive interest rate hikes and rising costs of living are pressuring more property owners to default, resulting in more mortgagee sales. It’s a prospect alluring to many property bargain hunters. However, hidden within the troubled title deeds of mortgagee sales can be caveats that can hinder the sale, or even more significantly impact subsequent buyers.

We spoke to property lawyer and College of Law lecturer Greg Stilianou to uncover what issues might impact mortgagee sales, why it’s important to address caveats early on, and what lawyers need to know when providing advice on a mortgagee sale.

What happens to a mortgagee sale if a caveat has been lodged?

A number of legal considerations come into play when a mortgagee sale involves a lodged caveat.

“When a mortgagee exercises their power of sale under section 58 of the Real Property Act 1900, they do so because the registered proprietor has defaulted on their mortgage obligations,” Greg explains. “This process often intersects with lodged caveats which, generally, prohibit the registration of subsequently lodged land dealings. The key issue is whether a caveat will prevent the registration of the mortgagee’s transfer and any other related dealings.”

For purchasers, this is the critical issue. Whether a caveat will prohibit registration of a mortgagee’s transfer requires closer examination of the caveat’s prohibitive effect.

“A standard form caveat does not prohibit the registration of a mortgagee’s transfer,” Greg says. “However, if the caveat is explicitly amplified to prohibit such a transfer (which a caveator is permitted to do under section 74H(5) of the Real Property Act 1900), it will need to be addressed before registration can proceed. Therefore, it is necessary to examine each lodged caveat that affects the subject land title to determine whether it will prohibit the registration of the mortgagee’s transfer, and if it doesn’t, what are the legal consequences for the caveat after the mortgagee’s transfer is registered.”

Why should you address a caveat early on?

A caveat can significantly impact the registration process.

“The Registrar-General treats all dealings in a lodgement case as a package,” Greg says. “If a caveat prevents one of the dealings in a lodgement case from being registered, the entire lodgment may be delayed or rejected. Therefore, it’s crucial to ensure that a caveat will not interfere with the registration of critical transactions, like the registration of a new mortgage after the mortgagee’s transfer.”

If you are unsure as to whether a caveat has been lodged, it’s important to find out as early as possible.

“The mortgagee’s sale contract typically includes clauses dealing with lodged caveats,” Greg says. “It is essential for the parties to agree on how any such caveat will be managed and by whom. If a caveat prevents registration, remedial action must be taken to avoid delays in the sale process.”

What remedial action is available if a caveat prevents registration?

A caveat may prohibit registration of a mortgagee’s transfer. If so, a purchaser has several options, including:

- Obtaining a Withdrawal of Caveat from the caveator.

- Applying for a Lapsing Notice through the land titles office.

- Seeking a court order for the Withdrawal of Caveat.

- Obtaining the caveator’s consent.

If a caveat does not prevent registration, what happens to a caveat when a mortgagee’s transfer is registered?

“Section 59 of the Real Property Act 1900 sets out the consequences,” Greg says. “It states that upon registration of the mortgagee’s transfer, the mortgagor’s estate vests in the transferee, free from liability under the mortgage and any subsequently registered mortgage, charge, or covenant charge. This extends to caveats where the claimed interest is in the nature of a mortgage, charge (excluding statutory charges), or covenant charge. Any such caveat will be removed from the Register without requiring a separate Withdrawal of Caveat.”

In some cases, a caveat can remain on title after the mortgagee’s transfer is registered.

“If the caveator claims an interest other than a mortgage, charge, or covenant charge, the caveat remains on the title,” Greg explains. “This means that any other dealings lodged alongside the mortgagee’s transfer, such as a new mortgage, could be blocked by the caveat.”

What happens if a caveat is under court supervision?

“If a caveat is subject to a lapsing notice and extended by a court order, the mortgagee may face difficulties in registering their transfer,” Greg says.

In such cases, as seen in Michael v Michael [2012] NSWSC 1216, the mortgagee should seek court intervention to:

- Join existing litigation between the registered proprietor and the caveator.

- Obtain a declaration that the mortgagee’s interest has priority.

- Secure an order requiring the caveator to withdraw the caveat.

- Ensure that earlier court orders extending the caveat are modified to allow the new orders to take effect.

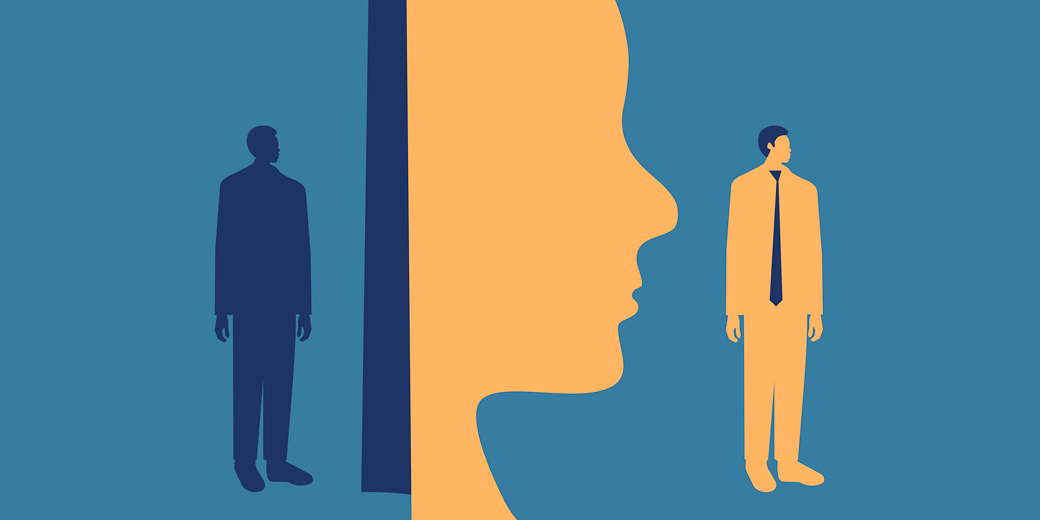

What should you do if you encounter a caveat in a mortgagee sale?

Firstly, it’s not the end of the world. It’s simply important to take a client through each stage in a methodical and clear-minded manner.

Should you encounter this situation, Greg advises considering the following decision-making process:

- Does the caveat prohibit the registration of the mortgagee’s transfer?

- If yes, remedial action is required.

- If no, proceed to the next step.

- Will the caveat be removed upon registration of the mortgagee’s transfer under section 59 of the Real Property Act 1900?

- If yes, the transaction can proceed.

- If no, consider whether the mortgagee’s transfer will be lodged with any other dealings that the caveat may prohibit, such as a new mortgage.

- If the caveat is under court supervision, legal intervention may be required.

![How to handle Direct Speech after Gan v Xie [2023] NSWCA 163](https://images4.cmp.optimizely.com/assets/Lawyer+Up+direct+speech+in+drafting+NSW+legislation+OCT232.jpg/Zz1hNDU4YzQyMjQzNzkxMWVmYjFlNGY2ODk3ZWMxNzE0Mw==)