The Honourable Robert Benjamin AM SC is no stranger to conflict. Having served for nearly sixteen years as a judge with the Family Court of Australia, Robert has also been a Commissioner for Tasmania’s Inquiry into Government Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Institutional Settings. It’s a career that has seen him navigate the complex human dynamics of the courtroom.

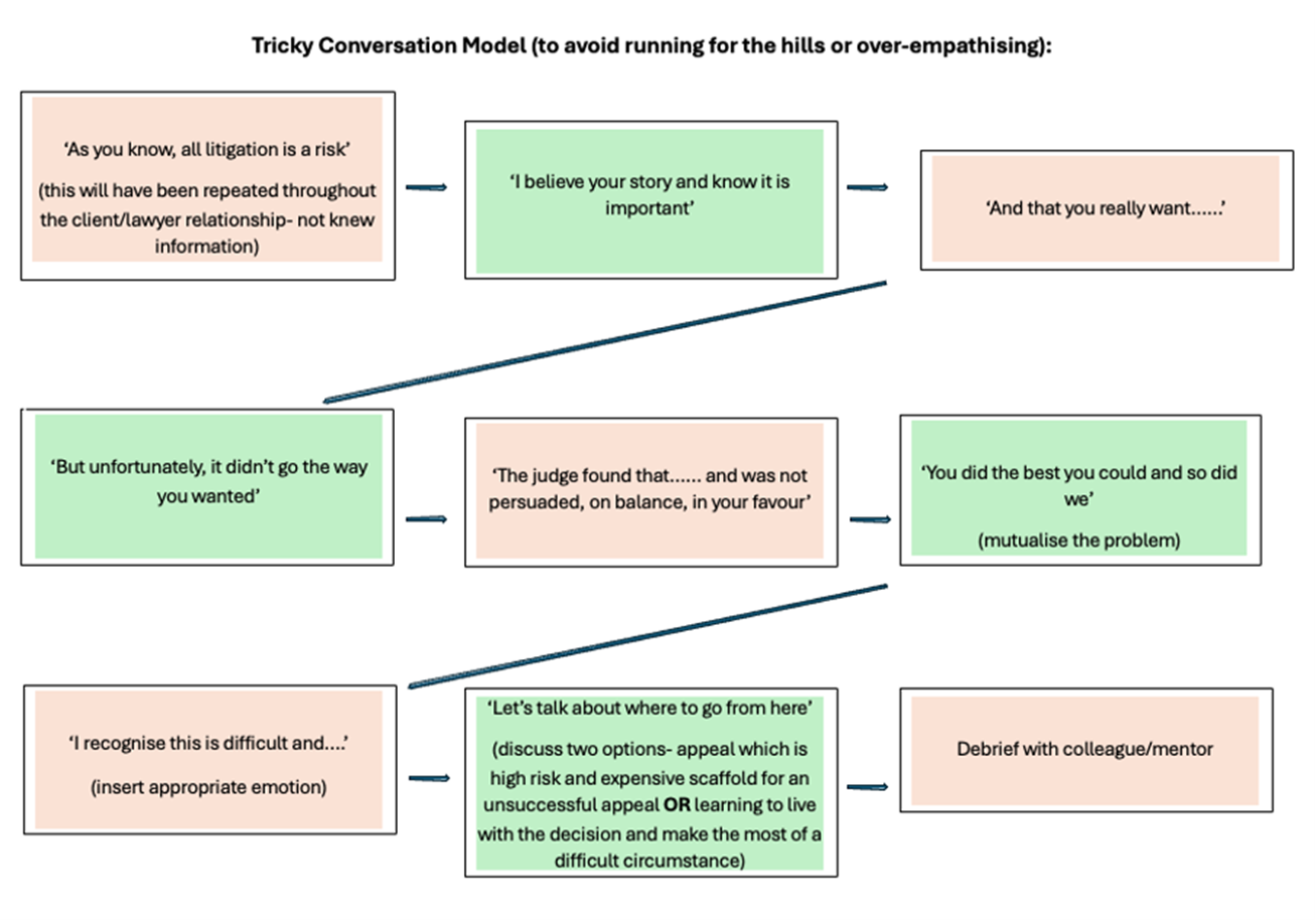

In this exclusive interview, Robert shares his practical framework to navigate tricky conversations, specifically designed to help lawyers deliver unwelcome news to clients - a methodology that balances honesty with empathy, and clarity with compassion. It’s a structured approach that enables, potentially confrontational interactions, to become constructive dialogues, revealing how proper preparation, mindful delivery, and thoughtful follow-up can preserve relationships while still conveying challenging truths.

The best case can be lost, and the worst case won

“Nothing is safe in law, particularly litigation,” Robert says. “The best case can be lost, and the worst case won.”

What is imperative is informing your clients and their supporters both early and regularly about this uncertainty, and preparing them for all outcomes.

“I have a model my daughter, Michelle, and I developed to navigate difficult conversations,” Robert explains. “Tricky conversations occur when a lawyer needs to give difficult information to another person, often a client, information they may not want to hear. This can lead to that person becoming emotionally dysregulated. It’s this outcome that can induce anxiety and avoidance on the part of the information giver.”

“The first step is the initial conversation. Here, you might say, ‘As you know all litigation is a risk,’” Robert says. “You would have repeated this throughout your relationship with your client, so this conversation is nothing new. The second step is to acknowledge the client by saying (if accurate), ‘I believe your story … I know it’s important,’ followed by, ‘And that you really want…’”

This allows sufficient emotional and contextual prefacing to deliver the difficult news.

“Here, you might say, ‘But unfortunately, it didn’t go your way…’ before detailing, with clear and unambiguous language, the outcome of the judgment,” Robert says. “At this stage, you can expect a client can really start to get emotionally dysregulated.”

Give them the story

What matters at this stage is to provide your client with the story – a narrative they can use to understand both the outcome of the case and how they can move forward with their lives.

You may say something along the lines of: ‘The judge found that…and was not persuaded, on balance, in your favour.’

“Now is your opportunity to mutualise the problem. For example, you could say, ‘You did the best you could, and so did we.’ Again, you’re giving them a story they can use to make sense of what’s happened,” Robert explains.

“By this stage, they’re probably not listening closely, and the client may become angry, crying, or in shock. You can and should acknowledge this – by saying, ‘I recognise this is difficult and [acknowledge their emotions]’.”

Finally, you can finish with a pragmatic outline of next steps.

“For example, you might say, ‘Let’s talk about where to go from here.’ Perhaps not now, but there are other options, to appeal, and risk an unsuccessful appeal. Or we can learn to live with the decision and make the most of it,” Robert says.

He added that you need to confirm the outcome and discussion in writing, immediately after the conversation.

In legal practice (and perhaps in life), you’ll invariably need to tackle difficult conversations from time to time.

“A structured conversation is preferable than avoiding passing on the bad news, dropping the bomb and running away, pretending nothing happened, or just sending your client the judgment,” Robert says. “As solicitors, we’re obliged to assess risk and convey to your clients that they can choose to go to court, and win, but also be informed of the consequences of losing. You need to talk your client through the costs involved, and the possibility of having to pay the other party's costs.”

“Always give your client a choice,” Robert urges. “The decision is theirs about whether to go to court, or if an offer to settle is made, whether to accept. You set these boundaries. This is a framework that hasn’t been taught that comprehensively, but can be very useful in practice.”

Prepare, prepare, prepare

Mastering the art of having difficult conversations comes down to preparation.

“A practical step is to prepare, prepare, prepare,” Robert says. “Sit down and do what you would do with any case. Write a plan. What are you going to say? How will you say it?”

“Try sitting with a colleague and have them yell at you as you practise what you’ve planned,” Robert suggests. “Practise the conversation in front of a mirror. This means you’re prepared for the conversation because you prepared for it.”

With colleagues prepare frank and clear answers and responses which may arise in the conversation.

Take the time to Debrief

However much you might prepare, a difficult conversation will still take an emotional toll on you. For some, this approach can help de-escalate any emotional dysregulation.

“For others, it doesn’t, because it’s become the centre of their lives for two to three years,” Robert explains. “For them, it’s disaster or another disaster.”

This is why Robert recommends a debrief to follow difficult conversations.

“You might have a full debrief if you’re in a partnership in a firm, or you may go and see a counsellor,” Robert says. “Choose someone you like, respect and trust (remember your duty of confidentiality still remains), and debrief properly, so you can give yourself some space. Don’t blame yourself. Know you’ve done the best you can do. Nobody in the world is perfect.”

"Often in my debriefs, with colleagues, I also look to consider - what have I learnt, what have I done well, what have I not done well, what changes can I make to my practice, understanding of my work and myself."

Remember: Be kind to your client and be kind to yourself.

Below is a suggested model and flow chart

Tricky Conversation Model

- A tricky conversation occurs when a lawyer needs to deliver difficult information that the other person does not want to hear.

- Tricky conversations often lead to the other person becoming emotionally escalated and dysregulated.

- This may induce anxiety within the information giver.

- This can lead to the information giver engaging in avoidance, bull at a gate’ or over-emphasising discussions.

- Prepare the conversation in the context of this structure.

![How to handle Direct Speech after Gan v Xie [2023] NSWCA 163](https://images4.cmp.optimizely.com/assets/Lawyer+Up+direct+speech+in+drafting+NSW+legislation+OCT232.jpg/Zz1hNDU4YzQyMjQzNzkxMWVmYjFlNGY2ODk3ZWMxNzE0Mw==)