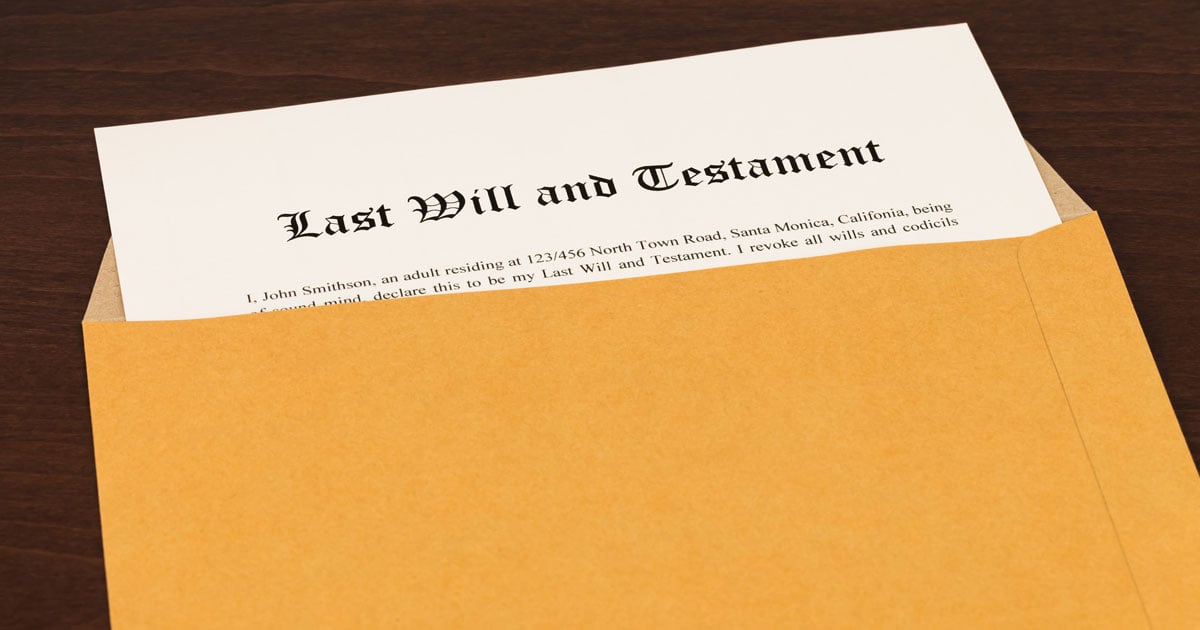

Major reforms to South Australia’s succession laws came into force on 1 January 2025. The new year saw the repeal of three Acts (the Administration and Probate Act 1919 (SA), the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1972 (SA) and the Wills Act 1936 (SA)), replacing these with a single Succession Act 2023. The most significant changes involve clarifying uncertainties regarding who can access a will, codifying aspects of the common law in relation to the payment of debts, provision of statutory remedies against executors or administrators who fail to perform their duties and most substantially, to family provision claims for parties claiming for further (or any) provision from an estate under a Will or the laws of intestacy.

We caught up with Megan Horsell, partner at DBH Lawyers and College of Law lecturer, to recap the most important changes now the Act has been in force for several weeks.

“The new Succession Act 2023 allows our work to be more streamlined because we have one rather than three Acts. This means we have one place to go and look for all we need, which is much more efficient,” Megan says. “It’s much more streamlined to just have one Act.”

Who has the right to inspect a copy of the will?

Prior to the new Succession Act 2023, there was some uncertainty surrounding who could access a will.

“Previously, a person with an interest in a will could ask the executor for a copy of the will, but there was no obligation on an executor to provide a copy. This resulted in high levels of conflict in some estates,” Megan says. “There could be a lot of tension and arguing which shouldn’t happen now.”

“The Succession Act 2023 provides a clear list of people who have a right to see the will,” she explains.

Below is the list provided in the Succession Act 2023 regarding who can see the will:

- Any person named or referred to in the will (regardless of whether they are a beneficiary);

- Any person named as a beneficiary in an earlier will of the deceased person;

- A surviving spouse, domestic partner, child, or step-child of the deceased;

- A former spouse or domestic partner of the deceased person;

- A parent or guardian of the deceased person;

- A person who would be entitled to share in the estate of the deceased on intestacy;

- A parent or guardian of a minor referred to in the deceased’s will or who would be entitled to a share of the deceased’s estate if they died intestate;

- A person committed with the management of the deceased’s estate under an administration Order immediately before the death of the deceased person; and

- Any other party who has a claim against the estate (at law or in equity), so long as they can demonstrate a ‘proper interest in the matter’ and inspection of the will is ‘appropriate in the circumstances’.

Simplifying how debts are settled

Before the reforms, settling the debts of an estate could be complicated and was governed by complex common law rules.

“Payment of debts could be a convoluted process, and it could be difficult to work out how debts would be paid from an estate,” Megan says.

“This is now set out step-by-step in the new Succession Act 2023. It will be much easier to work out what order debts should be paid in.”

Codifying how debts are paid will benefit executors and administrators, who now have clear guidance. This is expected to reduce delays in the administration of these estates.

Statutory remedy against an executor or administrator of an estate

Should an executor or administrator fail to perform their duties in the administration of an estate, the Succession Act 2023 provides for affected parties to apply for a Court order for the executor or administrator to pay funds to the estate. It also allows for any other order the Court considers appropriate, provided the application is made within three years of the date the aggrieved person became aware of the executor’s breach or failure in duties.

“Whilst this new provision provides an avenue for aggrieved parties to compel action from an executor or administrator, it may also cause angst for the executor or administrators of the estate given the 3-year time limitation,” Megan says, “we need to wait and see how this plays out.”

Family Provision Claims

The most significant changes introduced by the new Act concern family provision claims, specifically the eligibility criteria for claimants and the test provision to be applied by the Court.

Beyond the changes to claimant eligibility—including the addition of stepchildren and revised rules for grandchildren—the deceased's wishes are now the Court's primary consideration in family provision cases.

“Evidence of the deceased’s reasons for making no or limited provision must also be considered in actions commenced under the new Act,” Megan says. “These significant changes will affect how legal practitioners handle these cases, though their full impact will depend on guidance from the Court as it interprets the Act.”

More clarity to come this year

As the Succession Act 2023 is in its early days, more clarity will come as the new laws are applied.

“We’ve reviewed the Act, and we’re waiting to see what kind of instructions we get from clients,” Megan says.

“It will be interesting to see how the courts respond to the new laws. For example, one of the new criteria for making an inheritance claim is that the wishes of the deceased person be a primary consideration. This is reflected in the will, so this has always been the case, in a sense. We won’t know for some time how the court will interpret the new Act as cases come before it, so it is an exciting time for this area of law in South Australia.”

For more information on changes introduced by the Succession Act 2023, review our original interview with Megan Horsell here.

![How to handle Direct Speech after Gan v Xie [2023] NSWCA 163](https://images4.cmp.optimizely.com/assets/Lawyer+Up+direct+speech+in+drafting+NSW+legislation+OCT232.jpg/Zz1hNDU4YzQyMjQzNzkxMWVmYjFlNGY2ODk3ZWMxNzE0Mw==)